Inference for Means & Confidence Interval for µ

STAT 218 - Week 4, Lecture 3

Inference for Means

Important Symbols

To distinguish a quantitative variable from a categorical variable, we use different symbols to show population parameters and sample statistics.

Parameters

\(\mu\) = population mean

\(\sigma\) = population standard deviation

Statistics

\(\bar{x}\) = sample mean

\(s\) = sample standard deviation

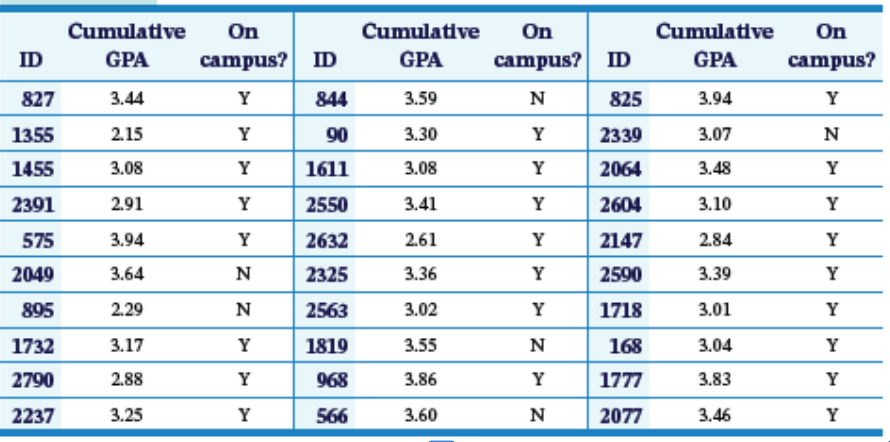

College Midwest - Example

- Let’s consider a situation (again) where we actually have access to the entire population.

- We recently obtained data on the student body of a small college in the Midwest.

- There are 2,919 students in this population.

- We will take a random sample of 30 students.

Observational Unit: A student in that college. Variable: Cumulative GPA Statistic: Sample Mean

College Midwest - Example

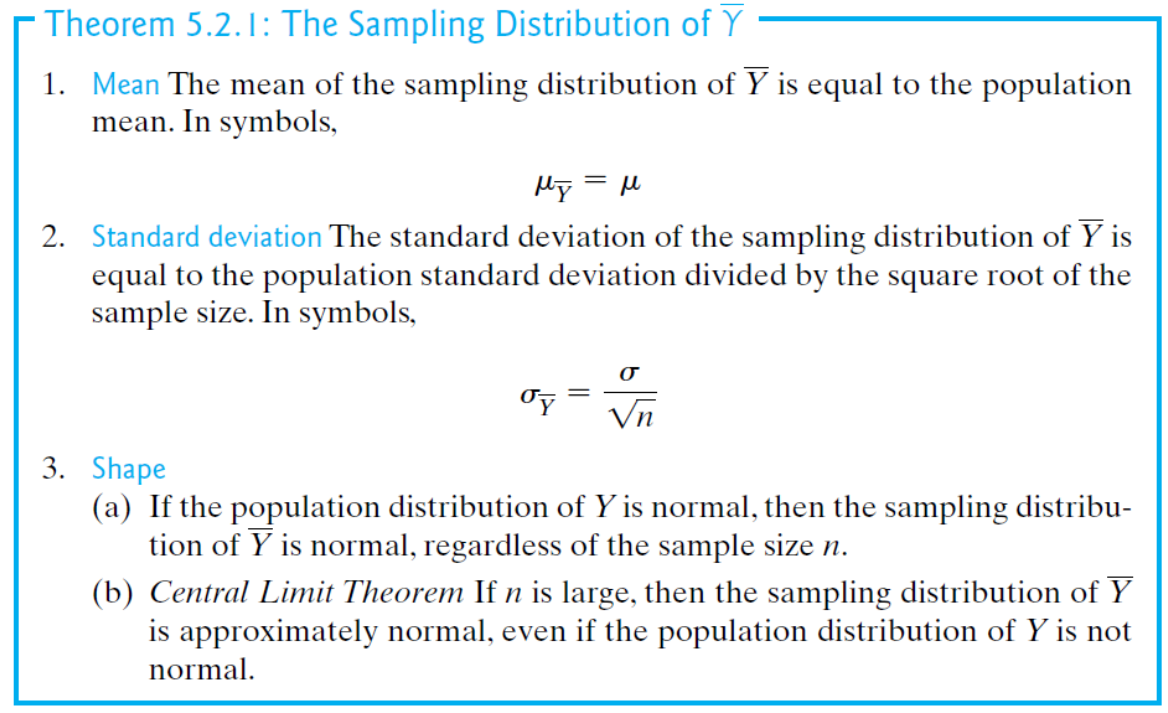

- Each simple random sample gave us a different value for the sample mean. Taking 1,000 random samples helps us see the long-run pattern to these statistics.

- In other words, we are approximating the sampling distribution of the sample means.

- Let’s see the applet to conduct a hypothesis testing

Central Limit Theorem fo Sample Means

Confidence Interval for µ

Introduction

In previous chapters, we were focusing on inferences about a population proportion (categorical variable).

Now, we will focus on data consisting of a single quantitative variable.

We will make inferences about a population mean (this is our new parameter now) by creating confidence intervals.

Confidence Interval Formula - Revisited

The general form of a confidence interval is

\[ \\ statistic \pm multiplier \times (SD \ of \ statistic) \]

Here, our statistic will be the sample mean and multiplier will come from t-distribution.

\[ \\ \bar{x} \pm t^* \times (s/ \sqrt{n}) \]

Student’s t distribution

What is t distribution?

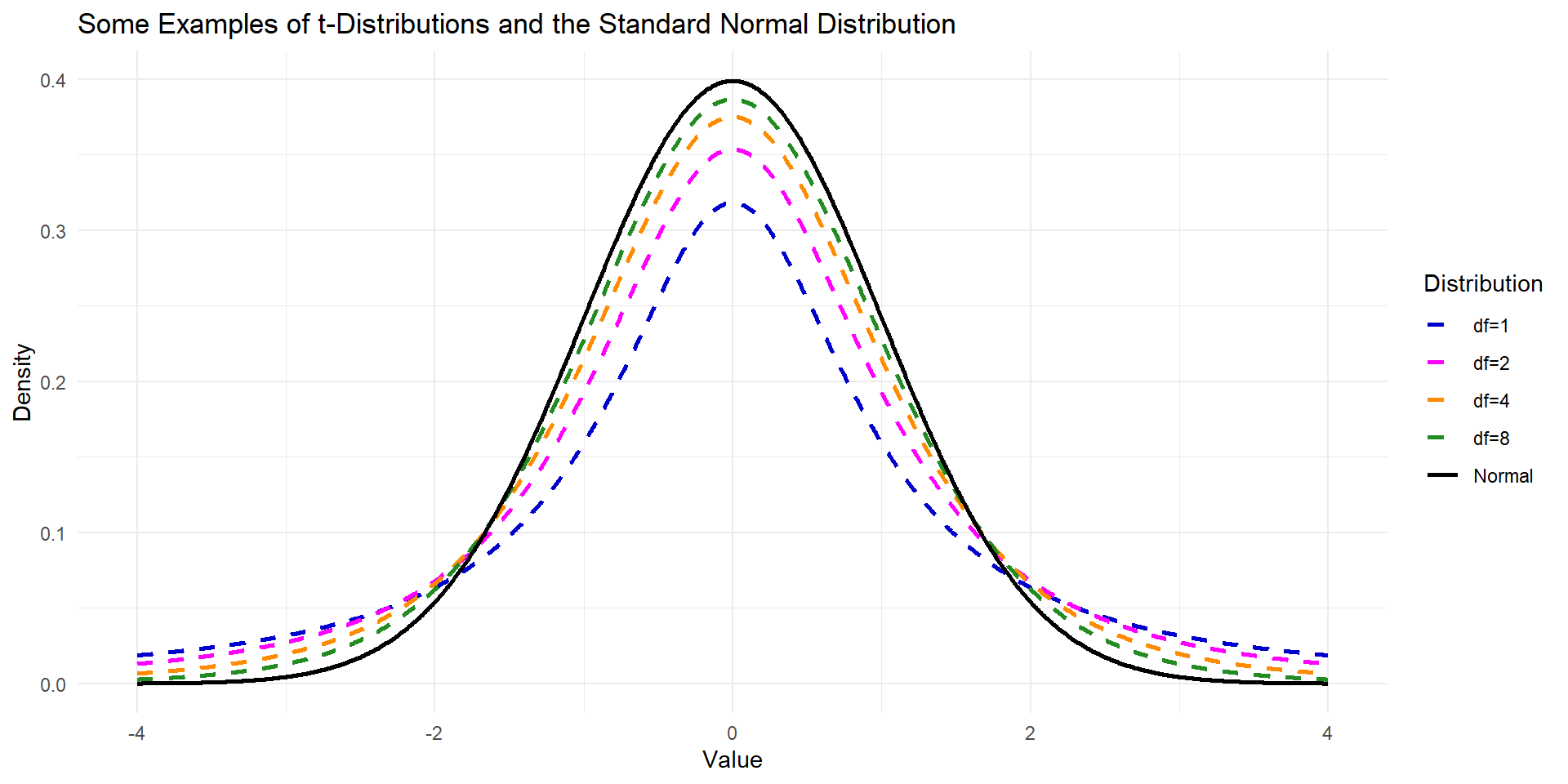

\(t\)-distribution is another bell shape and symmetric distribution that can be useful if we do not know anything about population parameters.

The \(t\)-distribution is always centered at zero and has a single parameter: degrees of freedom.

- The shape of the distribution depends on the degrees of freedom.

Broadly speaking, we use \(t\)-distribution with \(df = n − 1\)

- to model the sample mean when the sample size is \(n\).

- As the \(df\) is increasing, the \(t\)-distribution will look more like the standard normal distribution

- when the \(df\) is about 30 or more, the \(t\) -distribution is nearly indistinguishable from the normal distribution.

What is t distribution?

Comparison of t and the Standard Normal Distribution

Both are symmetric and bell-shaped but \(t\)-distribution has a larger standard deviation.

The \(t\)-distribution has a single parameter: degrees of freedom.

Standard Normal Distribution has two parameters: \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\).

Let’s Go Back to Confidence Interval

Monarch Butterflies - Example

Let’s have a look wing areas of 14 male Monarch butterflies at Oceano Dunes State Park in California

- \(\bar{x} = 32.81\) \(cm^2\) and \(s= 2.48\) \(cm^2\)

Suppose we consider these 14 observations as a random sample from a population.

- \(\mu\) = the (population) mean wing area of male Monarch butterflies in the Oceano Dunes region

- \(\sigma\) = the (population) SD of wing area of male Monarch butterflies in the Oceano Dunes region

Monarch Butterfly - Example

Let’s have a look wing areas of 14 male Monarch butterflies at Oceano Dunes State Park in California

- \(\bar{x} = 32.8143 \ cm^2\) and \(s= 2.4757 \ cm^2\)

For the multiplier, it is given as

\[ \\ multiplier = 2.160 \]

95% confidence interval (CI) for \(\mu\) can be calculated as following:

- \(\bar{x} = 32.8143 \ cm^2\) and \(s= 2.4757 \ cm^2\)

\[ \\95 \% \ CI = (\bar{x} \pm multiplier \ \times \ SE_{\bar{x}}) \\95 \% \ CI = (32.8143 \pm 2.160 \ \times \ 2.4757 / \sqrt{14}) \]

Monarch Butterfly - Example

90% confidence interval (CI) for \(\mu\) can be calculated as following (multiplier:1.771):

- \(\bar{x} = 32.8143 \ cm^2\) and \(s= 2.4757 \ cm^2\)

\[ \\90 \% \ CI = (\bar{y} \pm multiplier \ \times SE_{\bar{x}}) \\90 \% \ CI = (32.8143 \pm 1.771 \ \times \ 2.4757 / \sqrt{14}) \]

\[ \\= 32.81 \pm 1.17 \\ 31.64 \ cm^2 < \mu < 33.98 \ cm^2 \]

What were the differences between 90% CI and 95% CI?

Confidence Interval - Verbal Explanation

And…

If we calculate confidence intervals for each of these 100 samples, we will find that around 95% of these intervals capture the true population mean.

We are 95% confident that the true population mean is in this confidence interval.

Planning a Study to Estimate μ

Planning a Study to Estimate μ

- Before collecting data for a research study, it is wise to consider in advance whether the estimates generated from the data will be sufficiently precise.

- It can be painful indeed to discover after a long and expensive study that the standard errors are so large that the primary questions addressed by the study cannot be answered.

- The precision with which a population mean can be estimated is determined by two factors:

- the population variability of the observed variable Y, and

- the sample size.

Planning a Study to Estimate μ

- In some situations the variability of Y cannot, and perhaps should not, be reduced.

- For example, a wildlife ecologist may wish to conduct a field study of a natural population of fish; the heterogeneity of the population is not controllable and in fact is a proper subject of investigation.

- On the other hand, it is often appropriate, especially in comparative studies, to reduce the variability of Y by holding extraneous conditions as constant as possible.

- For example, physiological measurements may be taken at a fixed time of day; tissue may be held at a controlled temperature; all animals used in an experiment may be the same age

What sample size will be needed?

Recall that

\[ SE_{\bar{x}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}} \]

We can use this formula to determine our sample size as follows:

\[ Desired \ SE = \frac{Guessed \ SD}{\sqrt{n}} \]

Monarch Butterfly - Example

Suppose the researcher is now planning a new study of butterflies Monarch butterflies at Oceano Dunes State Park in California and has decided that it would be desirable that the SE be no more than \(0.4 \ cm^2\)

- \(\bar{y} = 32.8143 \ cm^2\) and \(s= 2.4757 \ cm^2\)

\[ SE_{\bar{y}} = s / \sqrt{n} \]

\[ Desired \ SE = Guessed \ SD / \sqrt{n} \]

\[ \\Desired \ SE = 2.48 / \sqrt{n} \ \le 0.4 \\ n\ge 38.4 \] \[ \\ at \ least \ 39 \ butterflies \]